While Glenn Mickens’ major league career consisted of four games with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1953, his impact on the sport was global, as he was one of the early Americans to play baseball in Japan. The long-time UCLA baseball coach who spent 13 seasons in professional baseball, died July 9, 2019, in Hawaii due to complications from pneumonia. He was 88.

For two years, he pitched for a semi-pro team while traveling with the Bruins before he signed a contract with the Dodgers in 1950. His early minor league career started a series of brushes with greatness throughout the vast Dodgers system. His first came with not a baseball legend, but a future NBA Hall of Famer, in teammate Bill Sharman.

“In 1951, we played [together] in Fort Worth,” Mickens said during a phone interview from his Hawaii home in 2011. “We would stop at every other ice cream parlor in the street when the streets were boiling and see who could eat the most ice cream. … He would be on the basketball court, and he would never miss. He always told me he liked baseball more than basketball. He slowed down from all that pounding on the basketball court. Obviously, he picked the right court.”

“I was in the medical corps down in Fort Sam Houston,” he said. “Bob Turley, Owen Friend, Gus Triandos, and Ken Staples [were there with me]. I think I was 16-1 the first year, and 18-4 the second. I got to stay in the United States. I am grateful for baseball. Our colonel had the power to put you on a boat to Korea.”

Upon his return, the Dodgers assigned Mickens to Fort Worth in the Texas League. Still relatively new to the ways of professional baseball, Mickens almost ruined his chances at the majors due to a seemingly innocuous comment he made to his manager.

“I made a stupid comment. … There was a guy on second base, and we were down by about seven runs. A guy gets a hit to right-center, and the outfielder throws the ball into one of the infielders. He didn't score.

“I said something to Max Macon like, ‘Darn skip, couldn't he have scored easy?’ He said, ‘Yeah that run doesn't mean anything.’ We lost 9-8 and like an idiot, I said, ‘Darn skip, that was a big run now, wasn't it?’ A rookie doesn't make those kinds of statements. I heard from the players that Max was going to leave me on the mound until my jockstrap was knocked off. ... He started pitching me with about two days rest [until] I got to the Dodgers.”

“I walk into that clubhouse from Fort Worth, and it was a doubleheader,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Which one of these is the seven-inning game, and which is the nine-inning game?’ [Roy] Campanella said, ‘Man this ain't no bush leagues! There ain't no seven-inning games here!’ I wanted to crawl under a stool.”

Dodgers manager Charlie Dressen wasted little time throwing Mickens into the fire. With Brooklyn down 2-1, Dressen sent Mickens to the mound in the top of the 9th inning against one of the National League’s top sluggers, Ted Kluszewski.

“I'll still never figure out that one,” he said. “Why Charlie brought me in to be the first guy I faced? I see this big guy [Kluszewski] with a couple of arms bigger than my legs. I said ‘Oh heck, I just don't want this guy to hit the ball back up the middle.’ I got one or two strikes on him, and I think I will keep the ball away and make him hit it. He hit the ball in the upper deck in Ebbets Field; I think he ripped up about five seats. I get back to the dugout and [Johnny] Podres was sitting there laughing. He said, ‘Don't feel bad, he hit 3 or 4 off of me—and I throw from the left side.’”

Mickens only lasted a few weeks in Brooklyn, as the Dodgers hit a hot streak and no longer had room for the rookie in their rotation. He cited Carl Erskine, Gil Hodges, and Duke Snider as a few who looked out for him during his time there. While his brush with The Boys of Summer was brief, it was in the Dodgers minor league system where Mickens built his relationships with baseball’s elite.

“He [Max Macon] had orders from the Dodgers, I found this out later, to try and hide him,” he said. “They would play him 4-5 innings, and they would take him out after he'd make a great catch or hit one over the right-center field fence. There wasn't anything he couldn't do.”

Another Dodgers legend that Mickens paired with was a fiery left-handed pitcher that went on to become a Hall of Fame manager, Tom Lasorda. The future Dodgers skipper had a mound tenacity that resonated with Mickens over 50 years later.

“If you had one big game on the line and you wanted to win it, you would give him the ball,” he said. “He had that 12-6 curve, and catchers would hate him because he would bounce it so often that he would beat the catcher to death. When he had to get it over though, he got it over. He would knock his own mom down if it meant winning a ballgame. Talk about a competitor; he was amazing.”

The Dodgers bounced Mickens all around their farm system, sending him to their affiliates in Los Angeles, St. Paul and Victoria, Texas. It was in Victoria where he sensed he needed a change. He reached out to an old friend, Ralph Kiner, who was the general manager of the San Diego Padres in the Pacific Coast League.

“I got to the airport [in Victoria], and I thought this was a place you go through, you don't get off there,” he said. “I said, trade me, sell me, or give me away. I called Kiner and said, ‘See if you can get me traded to the San Diego organization.’ He called me back and said, ‘Mick, they won't release you.’”

“My only chance at that stage of the game to get out of the organization was to go to Japan, which at that stage was outlaw ball,” he said. “Bill Nishida, who was in Montreal [with me], got me to go over there. I was over there for five years. I got in three All-Star Games and was the first and maybe only American to win an All-Star game for the three innings I pitched. I got to pitch against Sadaharu Oh over there. My only regret is that I didn't get another shot here.”

Baseball in Japan in the late 1950s was still in its formative stages. The level of play was nowhere near what it is today, and tactical methods were years behind as well. Mickens noted the stark contrast of how managers handled their players.

“Their regimen was so different,” he said. “These guys would last 4-5 years and would come up with sore arms. They would pitch nine innings and then be back in the game the next day if they were winning. … I was on the worst offensive and defensive club in Japan. The manager would ask me to throw 1-2 innings, and then [all of a sudden] you are out there 4-5 innings.

“There are so many things you have to get used to over there. I think they changed their methodology. They would not slide to break up the double play; they would run out of the way. Lefty O'Doul was doing some announcing over there. I told him I was trying to get them to play like back in the United States. He said, ‘Kid, forget it. I've been coming here for 30 years. They haven't changed, and they're not going to.’”

While Mickens could not always rationalize his team's tactical decisions, he recalled a hilarious method his manager once used to motivate him to close out the opposition.

“I'm on the bench one night and it's about the 8th inning,” he said. “The manager of our club, Chiba, he's trying to think of something to stimulate me to go out and finish the game to beat these guys. He said, ‘Remember Pearl Harbor!’” I almost fell off the bench.”

“There's a really cute story,” he said. “I faced Ralph Kiner. On the loudspeaker, after he hit his home run off me in Wrigley Field, the announcer said, ‘He hit this for his newborn baby boy, Mike.’ Twenty years later, I'm coaching at UCLA, and who am I coaching? Mike Kiner for crying out loud! I tell him, ‘Thank your dad for me.’ The other time I faced [Kiner] was in Ebbets Field. They said Kiner didn't strike out, but I struck him out in Ebbets. I remember the guy saying, ‘You can't strike Kiner out.’ He was a super nice guy.”

In retirement, Mickens moved to Hawaii where he was active in civic affairs and traveled the world with the UCLA alumni baseball team to compete in friendly exhibitions. While his time with the Dodgers only lasted four games, he realized the monumental achievement of just making the club.

“Who's place were you going to take up there?” he asked. “Duke Snider, Carl Furillo? They had these guys in front of you. What chance did you have?”

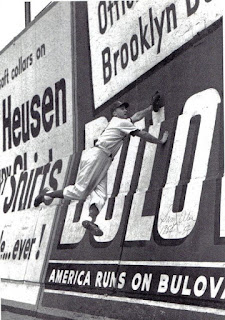

|

| Glenn Mickens / Author's Collection |

A False Start At UCLA

Mickens’ career hit a rocky start during his time at UCLA. Right before his 1948 freshman year, he went to a Brooklyn Dodgers tryout in Anaheim. While the Dodgers did not sign him, they told him they would keep an eye on him while he was at UCLA. Unfortunately, for Mickens, the scout running the camp gave him $20 for his food and travel. When Mickens went to UCLA, he reported on a questionnaire that he received the $20 from the Dodgers, and the NCAA ruled that he forfeited his amateur status.For two years, he pitched for a semi-pro team while traveling with the Bruins before he signed a contract with the Dodgers in 1950. His early minor league career started a series of brushes with greatness throughout the vast Dodgers system. His first came with not a baseball legend, but a future NBA Hall of Famer, in teammate Bill Sharman.

“In 1951, we played [together] in Fort Worth,” Mickens said during a phone interview from his Hawaii home in 2011. “We would stop at every other ice cream parlor in the street when the streets were boiling and see who could eat the most ice cream. … He would be on the basketball court, and he would never miss. He always told me he liked baseball more than basketball. He slowed down from all that pounding on the basketball court. Obviously, he picked the right court.”

Korean War Draft

Just as Mickens started to get comfortable with Sharman at Fort Worth, Uncle Sam called. Mickens received his draft notice for the Korean War, which caused him to miss the rest of 1951, as well as the entire 1952 season. Luckily, his baseball skills saved him from a potential fateful trip to Korea.“I was in the medical corps down in Fort Sam Houston,” he said. “Bob Turley, Owen Friend, Gus Triandos, and Ken Staples [were there with me]. I think I was 16-1 the first year, and 18-4 the second. I got to stay in the United States. I am grateful for baseball. Our colonel had the power to put you on a boat to Korea.”

Upon his return, the Dodgers assigned Mickens to Fort Worth in the Texas League. Still relatively new to the ways of professional baseball, Mickens almost ruined his chances at the majors due to a seemingly innocuous comment he made to his manager.

“I made a stupid comment. … There was a guy on second base, and we were down by about seven runs. A guy gets a hit to right-center, and the outfielder throws the ball into one of the infielders. He didn't score.

“I said something to Max Macon like, ‘Darn skip, couldn't he have scored easy?’ He said, ‘Yeah that run doesn't mean anything.’ We lost 9-8 and like an idiot, I said, ‘Darn skip, that was a big run now, wasn't it?’ A rookie doesn't make those kinds of statements. I heard from the players that Max was going to leave me on the mound until my jockstrap was knocked off. ... He started pitching me with about two days rest [until] I got to the Dodgers.”

A Call To The Brooklyn Dodgers

Luckily for Mickens, his jockstrap was intact, and his arm stayed attached long enough for the Dodgers to bring him to the majors in July 1953. Upon arriving, Roy Campanella immediately let him know that he was undoubtedly in the big leagues.“I walk into that clubhouse from Fort Worth, and it was a doubleheader,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Which one of these is the seven-inning game, and which is the nine-inning game?’ [Roy] Campanella said, ‘Man this ain't no bush leagues! There ain't no seven-inning games here!’ I wanted to crawl under a stool.”

Dodgers manager Charlie Dressen wasted little time throwing Mickens into the fire. With Brooklyn down 2-1, Dressen sent Mickens to the mound in the top of the 9th inning against one of the National League’s top sluggers, Ted Kluszewski.

“I'll still never figure out that one,” he said. “Why Charlie brought me in to be the first guy I faced? I see this big guy [Kluszewski] with a couple of arms bigger than my legs. I said ‘Oh heck, I just don't want this guy to hit the ball back up the middle.’ I got one or two strikes on him, and I think I will keep the ball away and make him hit it. He hit the ball in the upper deck in Ebbets Field; I think he ripped up about five seats. I get back to the dugout and [Johnny] Podres was sitting there laughing. He said, ‘Don't feel bad, he hit 3 or 4 off of me—and I throw from the left side.’”

Mickens only lasted a few weeks in Brooklyn, as the Dodgers hit a hot streak and no longer had room for the rookie in their rotation. He cited Carl Erskine, Gil Hodges, and Duke Snider as a few who looked out for him during his time there. While his brush with The Boys of Summer was brief, it was in the Dodgers minor league system where Mickens built his relationships with baseball’s elite.

Playing In The Minors With Baseball Legends

Playing with the Montreal Royals in 1954, his teammate was a young rookie outfielder named Roberto Clemente. He noted that while Clemente showed tremendous upside, the manager would remove him at odd times during the game. He later discovered why.“He [Max Macon] had orders from the Dodgers, I found this out later, to try and hide him,” he said. “They would play him 4-5 innings, and they would take him out after he'd make a great catch or hit one over the right-center field fence. There wasn't anything he couldn't do.”

Another Dodgers legend that Mickens paired with was a fiery left-handed pitcher that went on to become a Hall of Fame manager, Tom Lasorda. The future Dodgers skipper had a mound tenacity that resonated with Mickens over 50 years later.

“If you had one big game on the line and you wanted to win it, you would give him the ball,” he said. “He had that 12-6 curve, and catchers would hate him because he would bounce it so often that he would beat the catcher to death. When he had to get it over though, he got it over. He would knock his own mom down if it meant winning a ballgame. Talk about a competitor; he was amazing.”

A Regrettable Argument

While Mickens was busy making connections with baseball’s future icons, he was also working hard at getting back to the major leagues. After pitching well with Montreal in 1955, a frustrated Mickens had another run-in with management that sealed his fate within the Dodgers organization.“I had some words with Fresco Thompson,” he said. “I was with Wally Fiala. The rooms we were staying in were junior officers’ quarters in Vero Beach, just like the Army. Some [players] had been playing mumbly peg against the wall. … Thompson put a note on our door one day, and my roommate says, ‘Look at this; they’re going to take $20 out of our salary for wrecking these walls.’ I looked for him [Thompson] all over the camp, and I finally encountered him in the mess hall. I asked him if he signed it and he said, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘What right do you have to accuse me of something you don't know anything about?’ He said, ‘I've got my information.’ I said, ‘Tell me who your information is, and I'll call them a liar to their face.’ I was fuming. If he would have come up to me and asked, I would have told him, but he flat out accused me. He starts pointing his finger into my chest, and he said, ‘I'll send you so far down, it will take a $10 postcard to find you.’ I didn't realize it, but [after] that day, I could have won 20 games with Montreal, or anywhere in their organization, and I wouldn't have had another chance with the Dodgers.”

The Dodgers bounced Mickens all around their farm system, sending him to their affiliates in Los Angeles, St. Paul and Victoria, Texas. It was in Victoria where he sensed he needed a change. He reached out to an old friend, Ralph Kiner, who was the general manager of the San Diego Padres in the Pacific Coast League.

“I got to the airport [in Victoria], and I thought this was a place you go through, you don't get off there,” he said. “I said, trade me, sell me, or give me away. I called Kiner and said, ‘See if you can get me traded to the San Diego organization.’ He called me back and said, ‘Mick, they won't release you.’”

Heading To Japan

Mickens faced a situation that caused many of his peers to put aside their baseball dreams. With teams in full control of player contracts, their only other choice was to retire or leave the country. Mickens took the road less traveled, certainly by American players at the time.“My only chance at that stage of the game to get out of the organization was to go to Japan, which at that stage was outlaw ball,” he said. “Bill Nishida, who was in Montreal [with me], got me to go over there. I was over there for five years. I got in three All-Star Games and was the first and maybe only American to win an All-Star game for the three innings I pitched. I got to pitch against Sadaharu Oh over there. My only regret is that I didn't get another shot here.”

|

| Glenn Mickens 1960 Marusan Baseball Card / Japanese Baseball Cards |

Baseball in Japan in the late 1950s was still in its formative stages. The level of play was nowhere near what it is today, and tactical methods were years behind as well. Mickens noted the stark contrast of how managers handled their players.

“Their regimen was so different,” he said. “These guys would last 4-5 years and would come up with sore arms. They would pitch nine innings and then be back in the game the next day if they were winning. … I was on the worst offensive and defensive club in Japan. The manager would ask me to throw 1-2 innings, and then [all of a sudden] you are out there 4-5 innings.

“There are so many things you have to get used to over there. I think they changed their methodology. They would not slide to break up the double play; they would run out of the way. Lefty O'Doul was doing some announcing over there. I told him I was trying to get them to play like back in the United States. He said, ‘Kid, forget it. I've been coming here for 30 years. They haven't changed, and they're not going to.’”

While Mickens could not always rationalize his team's tactical decisions, he recalled a hilarious method his manager once used to motivate him to close out the opposition.

“I'm on the bench one night and it's about the 8th inning,” he said. “The manager of our club, Chiba, he's trying to think of something to stimulate me to go out and finish the game to beat these guys. He said, ‘Remember Pearl Harbor!’” I almost fell off the bench.”

A Return Home

Mickens finished up in Japan in 1963 and returned to UCLA to become their assistant baseball coach. He stayed for 25 years, fostering multiple generations of professional talent. He coached Eric Karros, Don Slaught, Tim Leary, as well as Ralph Kiner’s son, Mike, a connection to his brief major league stay.“There's a really cute story,” he said. “I faced Ralph Kiner. On the loudspeaker, after he hit his home run off me in Wrigley Field, the announcer said, ‘He hit this for his newborn baby boy, Mike.’ Twenty years later, I'm coaching at UCLA, and who am I coaching? Mike Kiner for crying out loud! I tell him, ‘Thank your dad for me.’ The other time I faced [Kiner] was in Ebbets Field. They said Kiner didn't strike out, but I struck him out in Ebbets. I remember the guy saying, ‘You can't strike Kiner out.’ He was a super nice guy.”

In retirement, Mickens moved to Hawaii where he was active in civic affairs and traveled the world with the UCLA alumni baseball team to compete in friendly exhibitions. While his time with the Dodgers only lasted four games, he realized the monumental achievement of just making the club.

“Who's place were you going to take up there?” he asked. “Duke Snider, Carl Furillo? They had these guys in front of you. What chance did you have?”